Don’t Be a Slave to the Training Plan: Use Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) to Guide Your Strength workouts

Anyone who has been strength training consistently has likely experienced how the same weight can feel heavier or lighter from one day to the next. You might come into a workout planning to deadlift 175 for 5 reps, something that is usually challenging but doable, but find that on that day you can barely do three reps with it. You double check the plates to make sure you (or your trainer) loaded the bar correctly, but unfortunately it is indeed 175. You feel like a failure and have an existential training crisis, question everything you’ve been doing, and the workout is ruined. But then the next week when you apprehensively attempt a set with the same weight the bar shoots up and you swear you could have done 10 reps no problem.

What’s going on here? No, you didn’t suddenly become weaker or stronger in just a few days. Rather, while the weights are the same, your body’s “readiness” to lift that weight has changed.

There are a number of factors that can influence our “readiness” to execute strength and endurance activities from one day to the next. These include:

How much and how well you slept

How much and how well you’ve eaten

Hydration

Stress (life, work, family, school)

Health (sickness, injury)

Accumulated training stress over the previous days and weeks

Small fluctuations in any of these usually won’t be noticeable in terms of how you feel in the gym, but big swings in these areas or periods of high physical and emotional stress can absolutely impact your readiness to lift.

Many stubborn individuals (myself included) will often attempt to complete a workout to the T regardless of how they feel, because that’s what the plan says they should do and they feel like a failure if they fall short. Then there are others who have become entirely reliant on wearable technology like rings and watches, and let their “recovery score” tell them how they should feel and dictate what workout they should do that day. And while the is nothing inherently wrong with wearable technology and template training plans, you should never take their recommendations over your own sensations and feelings. You know your body best, and learning how to listen to your body and adjust things on the fly based on how YOU feel in that moment is one of the most important skills you can develop as an athlete.

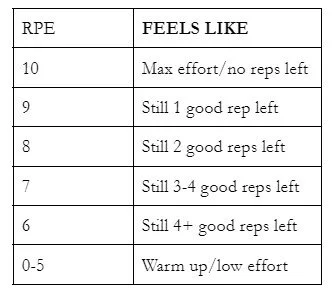

Training by RPE (rate of perceived exertion) is one way you can adjust your training in real time in response to how fresh or fatigued you are on that particular day. RPE is a subjective measure of the intensity of a lift, usually on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being little or no effort or and 10 being maximum effort. Put simply, it is how hard you feel like your body is working to execute a task. While I am using it in the context of strength training here you can certainly apply this framework to your endurance training as well.

Here’s what it can look like in a training session:

Go into the workout with an idea of the sets, reps, recovery, and RPE (not necessarily the weights) that you want to work up to on your 1-3 main lifts for that day. As an example, for hex bar deadlifts you could plan to work up to 3 sets of 5 reps with 2 minutes rest at an RPE 8. This means that you would select a weight during your main work sets that would leave approximately 2 good reps in the tank. While you might have an idea of what this weight will be based on what you did recently (maybe last workout was 175x3x5 at an RPE 8), what you actually work up today might be more or less depending on how you feel.

Pay attention to how you feel and how the bar is moving during the first few warm up sets. Note that it is helpful to keep the first 2-3 warm up sets the same every workout to help establish a baseline. Sticking with our hex bar deadlift example, you could do a couple light sets of 5 reps with 65, then move to 95, and finally 135, before you start to get to the heavier warm ups and working weights. Depending on how these first couple of sets go you can adjust your target working weights as necessary.

If your perceived exertion during the warm up sets feels higher than normal, then that could be a sign that you’re carrying some extra fatigue and should plan to reduce the weight of your working sets.

The opposite can also happen. If you feel really good during the warm up and the weights are flying off the floor, then you might be able to lift a little heavier than usual (note “a little,” not go for a new 1 rep max).

In both scenarios you are giving your body what it needs on that day and working at an intensity appropriate for your level of readiness. Even though the amount of weight lifted is different, your perception of that effort is about the same. 155 x 5 on a bad day might feel the same as 175 x 5 on a good day (an 8/10 RPE). Likewise, 175 x 5 in the off season when the endurance volume is low might feel a lot easier than 175 x 5 in the middle of summer when endurance volume or racing is high.

Understanding this is especially important if you are a self-coached athlete or if you’re following a template or percentage-based training plan. A plan that says today you’re lifting 85% of your 1RM for 5 reps isn’t entirely accurate. 85% on that day might actually be more like 80% if it’s a day you’re feeling good. Conversely, if you’re feeling really bad, that 85% could be more like 90% or even 95%. In either case, trying to execute the plan exactly as it is written might not be what’s best. Holding yourself back on a day you’re feeling good means you might not get what you needed or could have gotten out of that session. On the other hand, trying to lift more than you’re capable of on that day can cause you to miss lifts or worse get injured or dig yourself into a hole because you refused to listen to your body.

This is why learning how to lift by RPE (or rate of perceived exertion) is an important skill for self-coached and coached athletes alike if you want to keep making progress in your training. It is something that comes with time and experience though, and requires you to leave your ego at the door sometimes.

My first introduction to this kind of training was Jim Wendler’s 531. Like many strength programs, the weight and rep targets for the main lifts each workout based off of a certain % of your 1 rep max, and these would change week to week. However, the program gives you the option to make each individual workout harder or easier depending on how you felt and how hard you wanted to push the final set of the main lift on that day.

Choosing to do the bare minimum number of reps on that final set (5, 3, or 1, depending on the week) was great if you were feeling tired or the weight just seemed heavier than usual that day. This was still considered a successful workout, even if that’s all you did. However, if you were feeling really good and the weights were flying, you could go for as many reps as possible on that last set and even try to get a new rep PR. I really loved the flexibility of this program, as it allowed you to take advantage of the good days without the pressure of lifting too much or hard on the inevitable bad days.

As an endurance athlete you likely already do some form of this in your endurance training, too. If your workout calls for 4x4 min V02max intervals at X watts or heart rate, but the first effort felt way harder than it should have and you could barely complete it, you have a couple of options:

You could just try to grind out the last 3 exactly as prescribed, no matter what it takes.

You could reduce the power/heart rate so you can hit the time target.

You could reduce the time so you could hit the power/heart rate target.

You could do some combination of the two.

Or you could scratch the workout all together if you are feeling really bad and just go for an easy run or ride.

While it is nice to see the weight and reps gradually increasing over time, lifting less weight from one week to the next does not mean that your plan isn’t working, and shouldn’t be taken as a sign that you’re getting weaker or regressing. Progress is never linear, and day to day fluctuations are normal and to be expected.

Remember, at the end of the day you need to learn to listen to your body and adjust things in the moment as necessary. As Menachen Brodie writes in Lift Heavy Sh*t: “Through every set, every repetition, and every strength training session, the focus must always be on how you are moving, letting technique guide your weight selection for that day…Not what you did last week, or a month ago.”